X8: Making Choices

"Contrariwise," continued Tweedledee, "if it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn't, it ain't. That's logic." — Lewis Carroll (Through the Looking Glass)

It is our choices, Harry, that show who we really are, far more than our abilities. — J. K. Rowling (Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets)

So far, all the JavaScript code that you have written has been executed unconditionally. This means that the browser carried out statements in a set order, one after another. By entering different input values in text or number boxes, you could affect the results, but the code always went through the same steps and produced output of the same form.

Many programming tasks, however, require code that reacts differently under varying conditions. This capability is called conditional execution. For example, consider a Web page that converts a student's numerical course average to a letter grade. Depending upon the student's average, JavaScript code would need to assign a different letter grade (90 to 100 would be an A, 80 to 89 a B, and so on). Similarly, you might want to design a page that simulates dice rolls and distinguishes between rolls that are doubles or not. In this chapter, you will be introduced to the if statement, which is used to incorporate conditional execution into JavaScript code. After determining whether some condition is met, an if statement can choose among alternative sequences of code to execute — or can even choose to execute no code at all.

If Statements

Conditional execution refers to the code's ability to execute a statement or sequence of statements only if some condition holds true. The simplest form of conditional statement involves only one possible action. For example, if your code employs a variable to represent a student's grade on a test, you might want to include code that recognizes an A-level grade and congratulates the student. If their grade is not an A, no action should be taken. Conditional execution can also involve alternative JavaScript sequences triggered by related conditions. That is, the code can take one action if some condition is true, else take a different action if the condition is not true. For example, you might want your code to display one message for an A and another message for other grades. JavaScript if statements enable you to specify both these types of conditional execution.

The general form of an if statement is as follows, where the else case is optional:

if (BOOLEAN_TEST) {

STATEMENTS_TO_EXECUTE_IF_TRUE

}

else {

STATEMENTS_TO_EXECUTE_IF_FALSE

}

Upon encountering a JavaScript if statement, the browser's first action is to evaluate the test that appears in parentheses in the first line. The test can be any Boolean expression — that is, any expression that evaluates to either true or false. In JavaScript, Boolean tests are formed using relational operators, so named because they test the relationships between values. For example, the == operator tests for equality, so the Boolean expression (x == 5) would evaluate to true if the variable x stored the value 5 (else false). Similarly, the Boolean expression (y < 100) would evaluate to true if y stored a number less than 100 (else false). FIGURE 1 describes the JavaScript relational operators.

| Relational Operator | Comparison Defined by the Operator |

|---|---|

== | equal to |

!= | not equal to |

< | less than |

<= | less than or equal to |

> | greater than |

>= | greater than or equal to |

FIGURE 1. JavaScript relational operators.

EXERCISE 8.1: Referencing FIGURE 1 as needed, predict what each of the following Boolean expressions would evaluate to.

(true == true) (5 != 5) (6 > 6) (6 >= 6) (12 < 12) (12 <= 12)

The Boolean test at the beginning of an if statement determines which (if any) code will be executed. If the test succeeds (evaluates to true), then the code inside the subsequent curly-braces is executed. If the test fails (evaluates to false) and there is an else case, then the code inside the curly-braces following the else is executed. Note that if the test fails and there is no else case, then no statements are executed, and control moves on to the statement directly after the if statement. FIGURE 2 shows three if statements that distinguish between different student grades.

if (grade >= 90) {

messageP.innerHTML = 'Congratulations - you earned an A!';

}

|

if (grade < 90) {

diff = 90 - grade;

messageP.innerHTML = 'You need ' + diff + ' more points for an A.';

}

|

if (grade >= 90) {

messageP.innerHTML = 'Congratulations - you earned an A!';

}

else {

diff = 90 - grade;

messageP.innerHTML = 'You need ' + diff + ' more points for an A.';

}

|

FIGURE 2. Three examples of if statements.

- In the first example, the if test compares the grade to see if it is greater than or equal to 90. If so, the message "Congratulations - you earned an A!" is displayed. Since there is no else case, no action is taken if the grade is less than 90.

- The second example demonstrates that an if statement can control the execution of more than one statement. If the test succeeds (the grade is less than 90), then the statements inside the curly-braces are executed in order. In this case, the statements compute the difference between a 90 and the grade earned, then incorporate the difference in a message. If the grade is not less than 90, no action is taken.

- The third example combines the previous two, ensuring that a message is generated either way. If the grade is greater than or equal to 90, a congratulatory message is displayed. Otherwise, the browser will compute and display the difference between an A grade and the earned grade.

The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.1 contains the third if statement from FIGURE 2. When you enter a grade in the number box and click the button, the ShowA function is called to execute this statement and display a message based on the grade.

EXERCISE 8.2: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.1 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and entering different grades.

Many teachers will round their grades, so that a grade of 89.6 would round up to 90 and earn an A. Modify the HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.1 to round the grade before the if test statement is executed. Confirm that an 89.6 rounds up to an A, but 89.4 does not.

Designer Secrets

Designer Secrets

Although indentation and spacing in JavaScript code are ignored Web browsers, they are vitally important from the programmer's perspective. When you write an if statement, it is important to lay out the code so that its structure is apparent. Otherwise, later attempts to modify your code might introduce errors by misinterpreting which statements are controlled by the if and which are not.

For example, all three of the if statements in FIGURE 2 utilize spacing and indentation to make their structure clear. The closing curly-brace of each if or else case is aligned with the beginning of that case, whereas all statements inside the curly-braces are indented.

Input Verification

A common use of if statements in Web pages is for input verification. Many Web pages require you to enter inputs into text or number boxes, which are then used within the code. For example, the Grade-A page from EXAMPLE 8.1 includes a number box where you enter a grade. If you leave the box empty and click on the button, it is not clear what should be displayed (since there is no grade to process). An if statement can be used in situations like this to verify that input has been provided before processing.

The following if statement can be used in any page where user input in a text or number box is required. The Boolean test accesses the value attribute of the box and compares it with the empty string ''. If they are equal, meaning the box is empty, then a warning message is displayed in the page. If they are not equal, meaning something was entered in the box, the processing of that input can take place.

if (BOX_ID.value == '') {

DISPLAY_WARNING_MESSAGE

}

else {

PERFORM_DESIRED_ACTION(S)

}

The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.2 reimplements the Grade-A page (EXAMPLE 8.1) using an if statement of this form. If you click the button without entering anything in the box, the if test will evaluate to true and a warning message will be displayed. Otherwise, the statements that access the grade and display a message based on its value are executed as before. This example also shows that it is perfectly legal to nest one if statement inside another. When this occurs, proper indentation is essential to make the resulting code readable and straightforward to edit.

EXERCISE 8.3: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.2 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button. Confirm that the page displays a warning message if the button is clicked when there is no number in the box.

Currently, the page uses the generic 'point(s)' in the message displayed for a non-A. It would be nicer if it used the correct plurality, i.e., 'point' when the difference is 1 and 'points' for other differences. Add an if statement (with else case) so that the correct word is used in the message.

Common Errors to Avoid

Common Errors to Avoid

When performing input verification on a number box, it is important to use the value attribute instead of valueAsNumber. If you mistakenly specify the valueAsNumber attribute in the test, the comparison will not work as intended. This is due to fact that the valueAsNumber attribute of an empty box produces the special symbol NaN, which stands for "Not a Number." The symbol NaN cannot be directly compared using relational operators since it is not a real value.

This same pattern for verifying inputs can be used in many different pages. For example, consider the Tip page (EXAMPLE 6.3 from Chapter X6) for calculating the tip amount on a restaurant check. That page contained two number boxes where you entered a check amount and a percentage. Since the amount box did not have a default value, it would be easy for you to overlook the box and click the button without entering an amount. EXAMPLE 8.3 shows a reimplementation of the Tip page that uses an if statement for input verification. If amountBox is empty, the if test will return true and a warning message will be displayed. Otherwise, the code in the else case is executed — accessing the boxes, calculating the tip, and displaying it (as before).

EXERCISE 8.4: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.3 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and entering different amounts. Confirm that the page displays a warning message if the button is clicked when the amount box is empty.

Change the if test so that it accesses amountBox using the valueAsNumber attribute instead of value. What happens in the page?

EXERCISE 8.5: Many of the pages we considered in Chapter X7 could also utilize an if statement for input validation. Go back to the Metric Conversion page (EXAMPLE 7.1) and add input verification to the page. That is, a warning should be displayed if the button is clicked with an empty number box. Similarly, add input verification to the Pick-4 page (EXAMPLE 7.5).

Common Errors to Avoid

Common Errors to Avoid

A common mistake is to mistakenly use = instead of == when attempting to compare two values. Since = denotes an assignment, the browser will try to interpret the expression as an assignment statement. If the left-hand side is not a variable, an error will automatically occur. Assuming there is a variable on the left-hand side, however, the code will execute with unexpected behavior. If the expression on the right-hand side of the comparison evaluates to 0, false, or an empty string, the test will fail. Any other expression will make the test succeed. For example,

if (5 = x) { if (x = '') { if (x = 5) {

CAUSES_AN_ERROR NO_ERROR_TEST_FAILS NO_ERROR_TEST_SUCCEEDS

} } }

To avoid such odd behavior, always be careful to use the == operator when comparing values for equality.

Cascading if-else

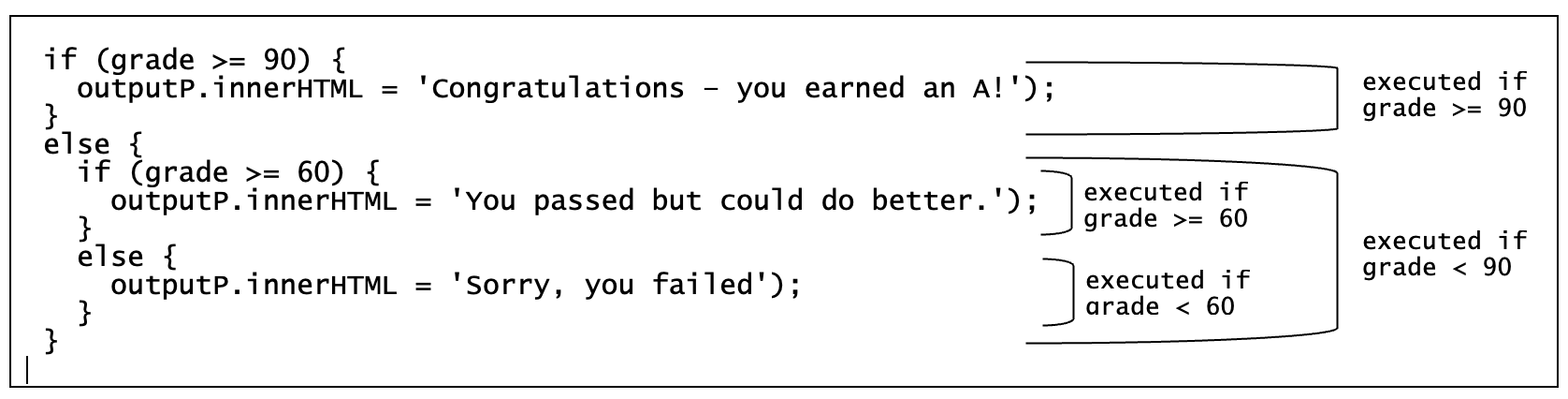

Often, programming tasks require code that responds to more than one condition. While a single if statement can only differentiate between two cases based on a single condition, multiple cases can be defined by nesting one if statement inside another. For example, the nested if statements in FIGURE 3 perform a three-way test on grades. The outer if statement differentiates between A's (grade >= 90) and non-A's (grade < 90). In the case of a non-A grade, a nested if statement further differentiates between passing (grade >= 60) and failing (grade < 60) grades.

FIGURE 3. Cascading if-else structure for classifying grades.

A nested if-else statement such as this is known as cascading if-else structure because control cascades down the structure like water down a waterfall. The topmost test is evaluated first — in this case: (grade >= 90). If this test succeeds, then the corresponding statement is executed, and control moves past the remaining cases. If the test fails, then control cascades down to the next if test — in this case: (grade >= 60). If there were more nested levels, control would cascade down the statement from one test to another until one succeeds, resulting in its statement being executed. If the structure ends with an else case, that case will execute unconditionally if it is reached (i.e., if all the tests above failed).

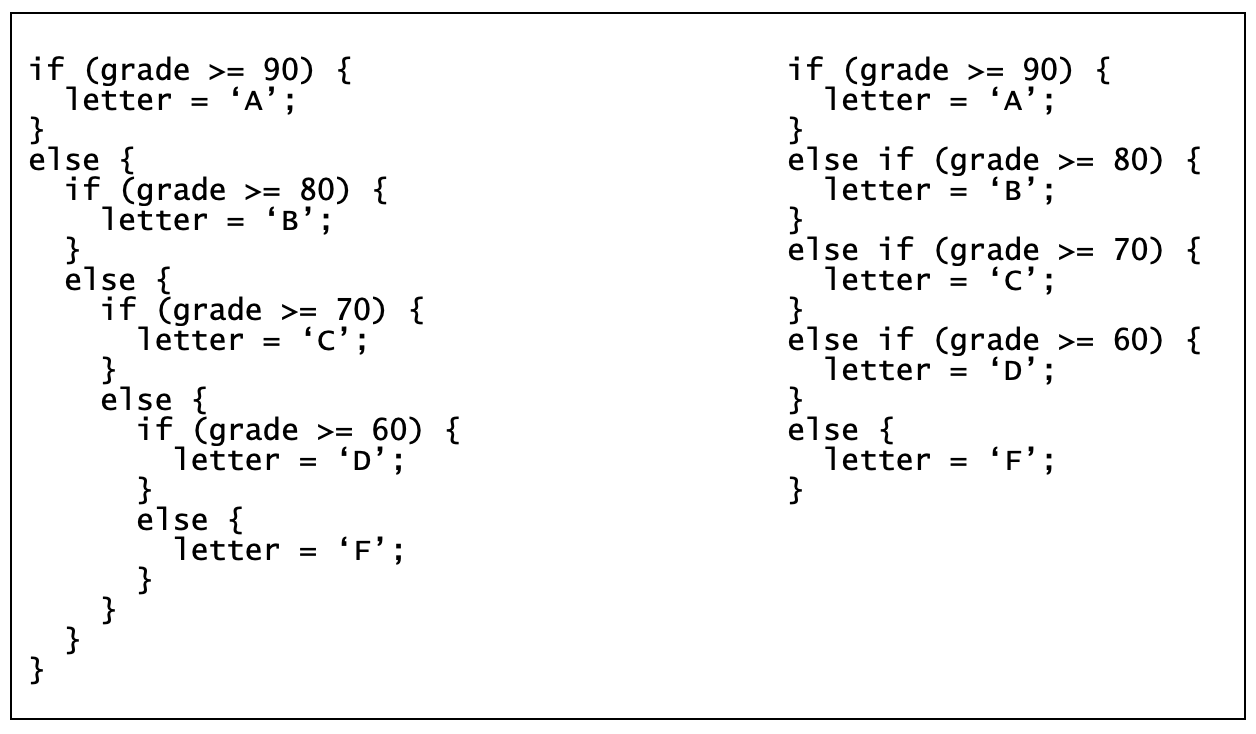

When it is necessary to handle many alternatives, cascading if-else structures can become cumbersome and unwieldy. This is because each nested if statement introduces another level of indentation and curly-braces, causing the code to look cluttered. Fortunately, programmers can write more concise, clearer cascading if-else structures by adopting a slightly different notation. The left-hand side of FIGURE 4 depicts a set of nested if statements that determine a student's letter grade using a traditional grading system. On the right is an equivalent code structure that is much more readable. This cleaner notation omits some unnecessary curly-braces and indents each case an equal amount. Using this notation, it is easier to discern that there are five alternatives, each assigning a letter grade based on grade's value.

FIGURE 4. Cascading if-else structure for assigning letter grades.

The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.4 uses the compact cascading if-else structure from the right of FIGURE 4 to identify and display a student's letter grade.

EXERCISE 8.6: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.4 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and entering different grades.

Similar to previous exercises, modify the HTML document from EXAMPLE 8.4 so that it (1) performs input verification and (2) rounds the grade to the nearest integer before testing.

Designer Secrets

Designer Secrets

An if statement is different from other JavaScript statements we have studied in that it does not perform an action in and of itself. Instead, it is known as a control statement, as its purpose is to control the execution of other statements. When solving problems, most programmers find it easy to determine when an if statement is required. If the code needs to make any choices during execution, i.e., react differently under different circumstances, then you need some version of an if statement.

- If the choice involves only one alternative, i.e., the code should carry out some action if a condition holds and do nothing if the condition does not hold, then a simple if statement is needed.

- If the choice involves two alternatives, i.e., the code should carry out some action if a condition holds and do something else if it does not hold, then an if statement with an else case is needed.

- If the choice involves more than two alternatives, i.e., the code should carry out one of three or more actions based on various conditions, then a cascading if-else structure is needed.

Global Variables

In previous chapters, you have used variables to store values from boxes and to save the results of calculations. These variables are known as local variables since their use was limited to a single function. When the function is called, that variable is initialized and used in computations, then discarded when the function call is complete. There are times, however, that you want variables to persist outside of any particular function.

Recall the Dice pages from Chapter X7, which used RandomInt (EXAMPLE 7.6) and RandomOneOf (EXAMPLE 7.7) from the random.js library to randomly select and then display dice rolls. In EXERCISE 7.8, you were asked to simulate repeated dice rolls using these pages and verify that doubles occurred roughly one-sixth of the time. This required you to keep track of not only the number of doubles obtained, but also the total number of rolls. It would be much more convenient and reliable if the page kept track of these counts automatically.

We could easily use variables to keep a count of the rolls and doubles. However, local variables will not suffice. The counts need to be initialized to 0 before any rolls are made, and any changes to the counts as a result of a roll must persist even after the function call is completed. What we need, instead, are global variables. A global variable is initialized within the script tags in the head of the page, but outside of any function. Since it is not local to a function, it is considered global, meaning it belongs to the entire page and persists as long as the page is active.

The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.5 utilizes a global variable to keep track of the number of dice rolls. The variable numRolls is initialized in the script element, outside of any function definition, which means that it is created and assigned a 0 when the page loads. When the "Click to Roll" button is clicked and the Roll function is called, it increments the count variable (numRolls = numRolls + 1;) and displays it in rollSpan. Because this variable is global, it persists after the function is done, which means additional clicks keep adding to the roll count. To make this page easier to use, a second function is defined to reset numRolls to 0.

EXERCISE 8.7: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.5 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and entering different grades. Be sure to test the "Reset" button to confirm that it resets the number of rolls.

A counter variable must be global, since its value must persist between function calls. Move the counter initialization (numRolls = 0;) inside the function and reload the page. What happens each time a roll is made?

Conditional Counters

A global variable that is initialized to 0 and incremented when an event occurs (e.g., numRolls) is known as a counter. Counters can be combined with if statements to count conditional events, i.e., events that occur only under certain circumstances. For example, in addition to counting the total number of dice rolls, we might also want the DiceCount page from EXAMPLE 8.5 to automatically record how many times doubles occur. This will require conditional execution, because the counter corresponding to doubles should be incremented only on the condition that the two dice rolls are the same. The following if statement will accomplish this conditional increment (assuming that numDoubles has been created and initialized to 0):

if (roll1 == roll2) {

numDoubles = numDoubles + 1;

}

Similarly, if we wanted to count the number of times the dice total seven, we could add a second if statement that similarly tests for a sum of seven (assuming that numSevens has been created and initialized to 0):

if (roll1+roll2 == 7) {

numSevens = numSevens + 1;

}

If we wanted to count both doubles and sevens, we could add both if statements to the Roll function. Alternatively, we could note that doubles and sevens are exclusive — if a roll is a double, it can't also total seven. As a result, we could combine the two if statements into a single cascading if-else structure:

if (roll1 == roll2) {

numDoubles = numDoubles + 1;

}

else if (roll1+roll2 == 7) {

numSevens = numSevens + 1;

}

When this cascading if-else structure is executed, it first checks to see if the rolls are identical. If so, numDoubles is incremented. If not, the second test is evaluated to see if the rolls add up to seven. If they do, numSevens is incremented. Note that there is no else case for this structure. Thus, if the roll is neither doubles nor a seven, no action takes place and the counts are unaffected.

The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.6 adds two global variables named numDoubles and numSevens to keep track of the number of doubles and sevens rolled, respectively. The cascading if-else structure from above is added in the function to update the global variables appropriately. Note that the Reset function is also updated to reset the new counters.

EXERCISE 8.8: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.6 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and entering different grades. Be sure to test the "Reset" button to confirm that it resets all the counts.

Since you no longer need to count the doubles yourself, it should be easier to simulate a large number of rolls and report the number of doubles. Simulate 60 rolls and see if you obtain the expected number of doubles (10) and sevens (10). Reset the counts and simulate another 60 rolls. How consistent are the results you obtained from the two experiments?

Boolean Operators

So far, all the if statements we have seen involved simple tests. This means that each test contained a single comparison using one of the Boolean operators. In more complex applications, however, simple comparisons between two values may not be adequate to express the conditions under which code should execute. Suppose, for example, that you wanted to count the number of times that both die faces display four dots (we call this a 4-4 combination). Simply testing the sum of the two die faces would not suffice, as this would not distinguish between 4-4 and other combinations that total 8, such as 3-5 and 2-6. Instead, the values of both die faces must be tested to determine that they are both 4s.

One option for creating this type of two-part test is to nest one if statement inside another. Because the browser evaluates the nested if statement only if the outer test succeeds, the code inside the nested if statement is executed on the condition that both tests succeed. For example,

if (roll1 == 4) {

if (roll2 == 4) {

CODE_TO_BE_EXECUTED_IF_4-4_COMBINATION_IS_ROLLED

}

}

Fortunately, JavaScript provides a more natural and compact alternative for expressing multipart tests. The AND operator (&&), when placed between two Boolean tests, represents the conjunction of those tests. In other words, the Boolean expression (TEST1 && TEST2) will evaluate to true if TEST1 is true AND TEST2 is true. For example:

if (roll1 == 4 && roll2 == 4) {

CODE_TO_BE_EXECUTED_IF_4-4_COMBINATION_IS_ROLLED

}

Similarly, the OR operator (||), when placed between two Boolean tests, represents the disjunction of those tests. In other words, the Boolean expression (TEST1 || TEST2) will evaluate to true if either TEST1 is true OR TEST2 is true. For example,

if (roll1 == 4 || roll2 == 4) {

CODE_TO_BE_EXECUTED_IF_EITHER_ROLL_IS_4

}

Finally, the NOT operator (!), when placed before a Boolean test, represents the negation of that test. In other words, the Boolean expression (!TEST) will evaluate to true if TEST is NOT true. For example,

if (!(roll1 == 4 && roll2 == 4)) {

CODE_TO_BE_EXECUTED_ IF_4-4_COMBINATION_IS_NOT_ROLLED

}

The &&, ||, and ! operators are known as logical connectives, because programmers use them to build complex logical expressions by connecting simpler logical expressions. It is important to note that logical connectives must be applied to complete Boolean expressions. For example, (roll1 == 3 || roll1 == 4) is a legal expression, but (roll1 == 3 || 4) is not.

In gambling circles, the combination of a 3 and 4 (in either order) is known as a natural seven. The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.7 augments the EXAMPLE 8.6 page to also keep track of the number of natural sevens that are rolled. Note that the if statement that identifies natural sevens appears inside the if case that identifies sevens. This means that the natural seven test only occurs after the page has already determined that a seven has been rolled. Thus, it suffices to determine whether roll1 is either a 3 or a 4.

EXERCISE 8.9: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.7 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and simulating repeated rolls.

Simulate 100 dice rolls by repeatedly clicking on the button. How frequently would you expect to obtain a natural seven? Do the results of your repeated simulations match your expectations?

EXERCISE 8.10: The Tip page from EXAMPLE 8.3 added an if statement to verify that a number had been entered into the amount box. The percent box was not checked on the assumption that the default value would make an empty box unlikely. It is possible, however, for you to verify the contents of both boxes. This can be done neatly using the Boolean connective ||.

if (amountBox.value == '' || percentBox.value == '') {

tipP.innerHTML = 'You must enter numbers in the boxes.';

}

else {

SAME_CODE_AS_BEFORE

}

Update the HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.3 page to include an if statement of this form that verifies that numbers have been entered into both number boxes. Test your modification to be sure it behaves as desired.

Putting It All Together

Using the ESP pages from EXAMPLES 7.9 and 7.10, you were able to measure your ESP ability (really your luck). The pages contained three buttons, labeled 'Guess 1', 'Guess 2', and 'Guess 3'. When you clicked on a button, your guess was compared with a randomly selected number and a message of the form 'The number was X. You guessed Y.' was displayed. While that was fine for processing a single guess, making repeated guesses and keeping track of the correct ones would be tedious.

The Dice examples from this chapter added counters (global variables initialized to 0 when the page loads) and updated those counters when the desired rolls occurred. We can make the same additions to the ESP page to keep track of the number of correct guesses and the total number of guesses made. The HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.8 does this.

There are several details to note about this document and how it implements the desired appearance and behavior of the page.

- Similar to the counters added to the Dice page, counters named

numCorrectandnumGuessesare initialized in thescriptelement. Since the variables are initialized outside of any function, they are global and so will persist as long as the page is in use. - Similar to the way that the dice counters are updated in the

Rollfunction, thenumCorrectandnumGuessescounters are incremented as needed within theGuessfunction. ThenumGuessescounter is incremented unconditionally, since each call to the function represent another guess. ThenumCorrectcounter is only incremented if the guess matches the randomly chosen number. - To simplify the output, a variable named

outcomeis introduced. When the two numbers are compared, the outcome is assigned to the variable, either 'CORRECT!' or 'Sorry, it was X.', where X is the random number. This variable is embedded in the message that is displayed in the page, along with the counts.

While this page now keeps track of correct and total guesses, testing your ESP/luck still requires considerable work on your part. Because there are three possible numbers to guess, you would expect random guesses to be correct one out of three times (33.3%). To see if you have ESP/luck, you would need to calculate your percentage of correct guesses and compare that percentage against 33.3%. Fortunately, we can add features to the page to automate this work.

Note the following about this updated document:

- Calculating the percentage of correct guesses is straightforward — divide the number of correct guesses by the total number of guesses, then multiply by 100.

- Determining whether you exceeded expectations requires an if statement with an else case. If your percentage is greater that 100/3 = 33.3%, you might have ESP (or were just lucky), Otherwise, there is no evidence of possible ESP (or you were unlucky). The outcome is assigned to the variable you didn't. Based on this comparison, the outcome is assigned to the

judgementvariable which is then displayed as part of the final message.

EXERCISE 8.11: Confirm that the Web page from EXAMPLE 8.9 behaves as described by clicking the "See in Browser" button and simulating repeated guesses.

Make 5 guesses within the page — what is your percentage correct? Would it surprise you if you exceeded 33.3%? Next, reset the counts and make 50 guesses in the page — what is your percentage correct? Would it surprise you if you exceeded 33.3%?

EXERCISE 8.12: Modify the HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.9 so that it has a 'Reset' button, similar to the ones in the Dice pages. When clicked, this button should call a function to reset all the counters and erase the message in the page. Test your modified page to confirm that it behaves as desired.

EXERCISE 8.13: Modify the HTML document in EXAMPLE 8.9 so that it allows guesses from 1 to 4 (instead of 1 to 3). This will involve adding a new button, modifying the call to RandomInt that picks the number, and updating the percentage test. Test your modified page to confirm that it behaves as desired.

Chapter Summary

- Conditional execution refers to the code's ability to execute a statement or sequence of statements only if some condition holds. In JavaScript, conditional execution is performed using if statements.

- The general form of an if statement is as follows, where the else case is optional:

if (BOOLEAN_TEST) { STATEMENTS_EXECUTED_IF_TRUE } else { STATEMENTS_EXECUTED_IF_FALSE }If the Boolean test succeeds (evaluates to true), then the browser executes the code inside the subsequent curly-braces. If the test fails (evaluates to false) and there is an else case, then the code inside the curly-braces following the else is executed. - The following relational operators can be used to build simple Boolean expressions:

==(equal to),!=(not equal to),<(less than),<=(less than or equal to),>(greater than), and>=(greater than or equal to). - If statements are commonly used in Web pages to verify that an appropriate input value has been entered into a text or number box before attempting to process that input.

- Programmers can write code that chooses among an arbitrary number of alternative cases by using a cascading if-else structure, which is really nothing more than a series of nested if statements. The general form is as follows:

if (TEST1) { STATEMENTS_EXECUTED_IF_TEST1_SUCCEEDS } else if (TEST2) { STATEMENTS_EXECUTED_IF_TEST2_SUCCEEDS } else if (TEST3) { STATEMENTS_EXECUTED_IF_TEST3_SUCCEEDS } . . . else { STATEMENTS_IF_ELSE } - A variable initialized and used within a single JavaScript function is local to that function. The variable only exists while that function is executing.

- A global variable is a JavaScript variable that is assigned an initial value outside of any function. The variable is initialized when the page is loaded and persists throughout the lifetime of the page.

- A Boolean expression involving the

&&operator will evaluate to true if both of its components evaluate to true, e.g., if variablexstores the value 84, then(x>=80 && x<90)would evaluate totrue. - A Boolean expression involving the

||operator will evaluate to true if either of its components evaluate to true, e.g., if variablexstores 3, then(x==3 || x==4)would evaluate totrue. - A Boolean expression involving the

!operator will evaluate to true if the expression following the operator is not true, e.g., if variableteststorestrue, then(!test)would evaluate totrue.

Projects

All projects should follow the basic design guidelines described in this and the previous chapters. These include:

- If a choice needs to be made, an appropriate if statement should be used: one way choice → if (with no else); two-way choice → if-else; multi-way choice → cascading if-else structure.

- The closing curly-brace

}in an if or else case should align with the beginning of the case. Any statements within a case should be indented for readability. - A global variable should be used to store a value that persists within the page; a local variable should be used for temporary variables within a function.

- The Boolean operators (

&&,||and!) should be used whenever possible to simplify the structure of a cascading if-else structure.

PROJECT 8.A: Project 7.A asked you to modify the original ESP page (EXAMPLE 7.10) to utilize two number boxes. The first should specify the range of possible numbers (e.g., 4 in the box would cause the page to generate random integer in the range 1..4). The second number box holds your guess. By entering a guess and clicking the button, the function was called to see if your guess was correct.

Download a copy of the ESP page from EXAMPLE 8.9 (by clicking on the Download link) and save it on your computer under the name esp2.html. Using a text editor of your choice, modify the document so that so that it similarly uses the two number boxes as described above. If the number box is empty or the entered number is not in the expected range, then a warning message should be displayed and the guess ignored.

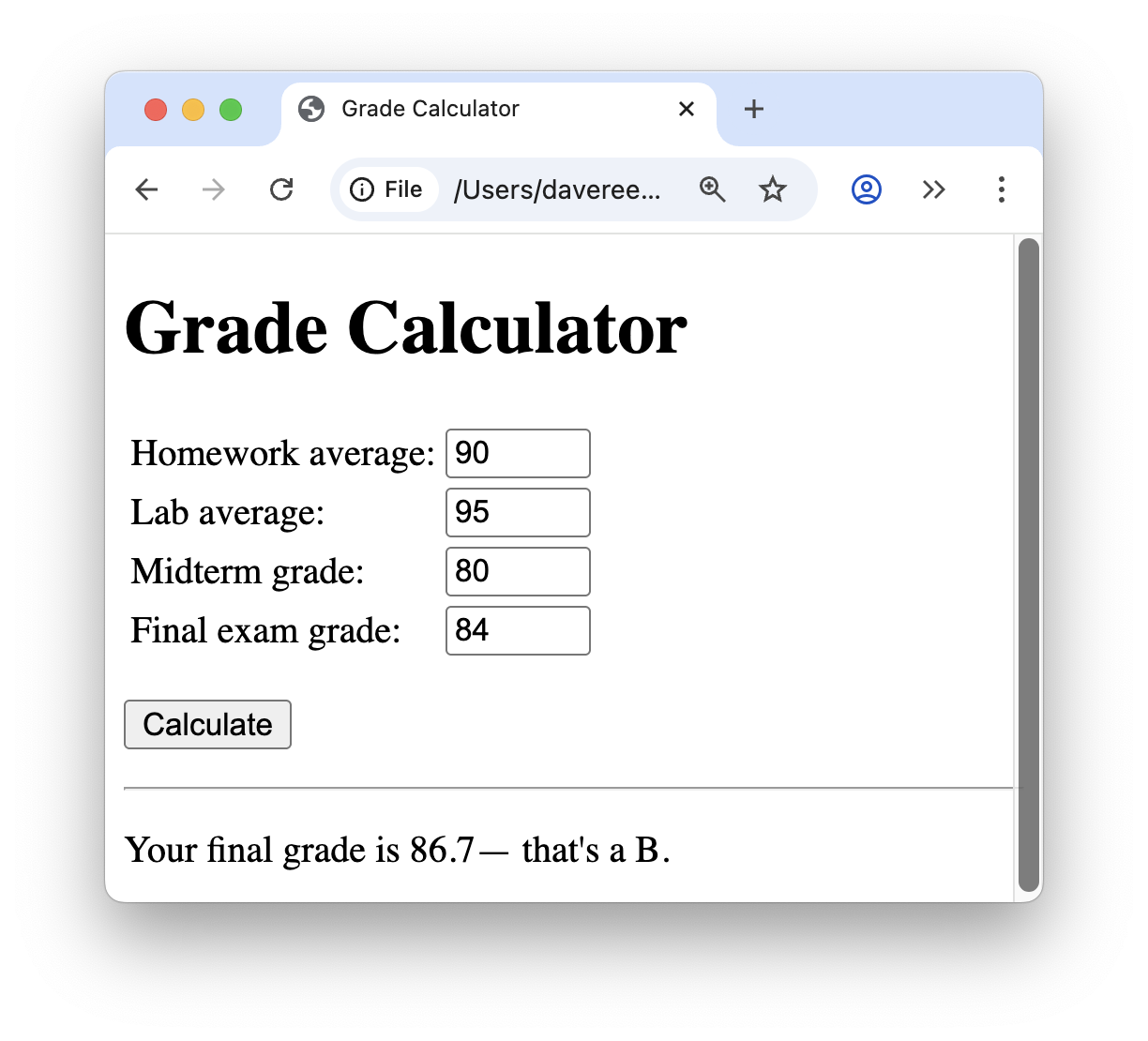

PROJECT 8.B: Project 6.C asked you to create a Web page that calculated a student's average in a course. There were number boxes where the student could enter their homework and lab averages along with their midterm and final exam scores. When the button was clicked, a function accessed those numbers and calculated their overall course average.

If you have completed this project already, start with the HTML document you created. If not, complete that project and save your document under the name grades.html. Then, make the following modifications:

- Add input verification to the page. That is, if any of the four boxes are empty, a warning message should be displayed in the page. Otherwise, the weighted average should be calculated and displayed as before.

- Add a cascading if-else statement (similar to the one in EXAMPLE 8.4) that displays the letter grade earned by the student. When displaying the grade, the appropriate article (either 'a' or 'an') should be used: 'an' for A and F letter grades; 'a' for B, C and D letter grades.

For example,

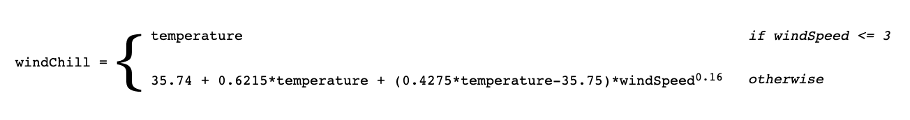

PROJECT 8.C: During cold weather, temperature is not always the best indicator of how extreme the conditions are. On a still day, a temperature of 20° Fahrenheit might feel comfortable, whereas that same temperature with a 30 miles-per-hour wind might seem frigid. To better measure how the weather feels to an exposed person, meteorologists developed the wind chill index, whose definition is given below (where temperature is in degrees Fahrenheit and wind speed is in miles-per-hour):

Note that if conditions are calm (wind speed is less than or equal to 3 miles per hour), the wind chill index is the same as the temperature. Otherwise, a complex formula involving temperature and wind speed is used. Also, it should be noted that wind chill is not defined for temperatures above 50° Fahrenheit.

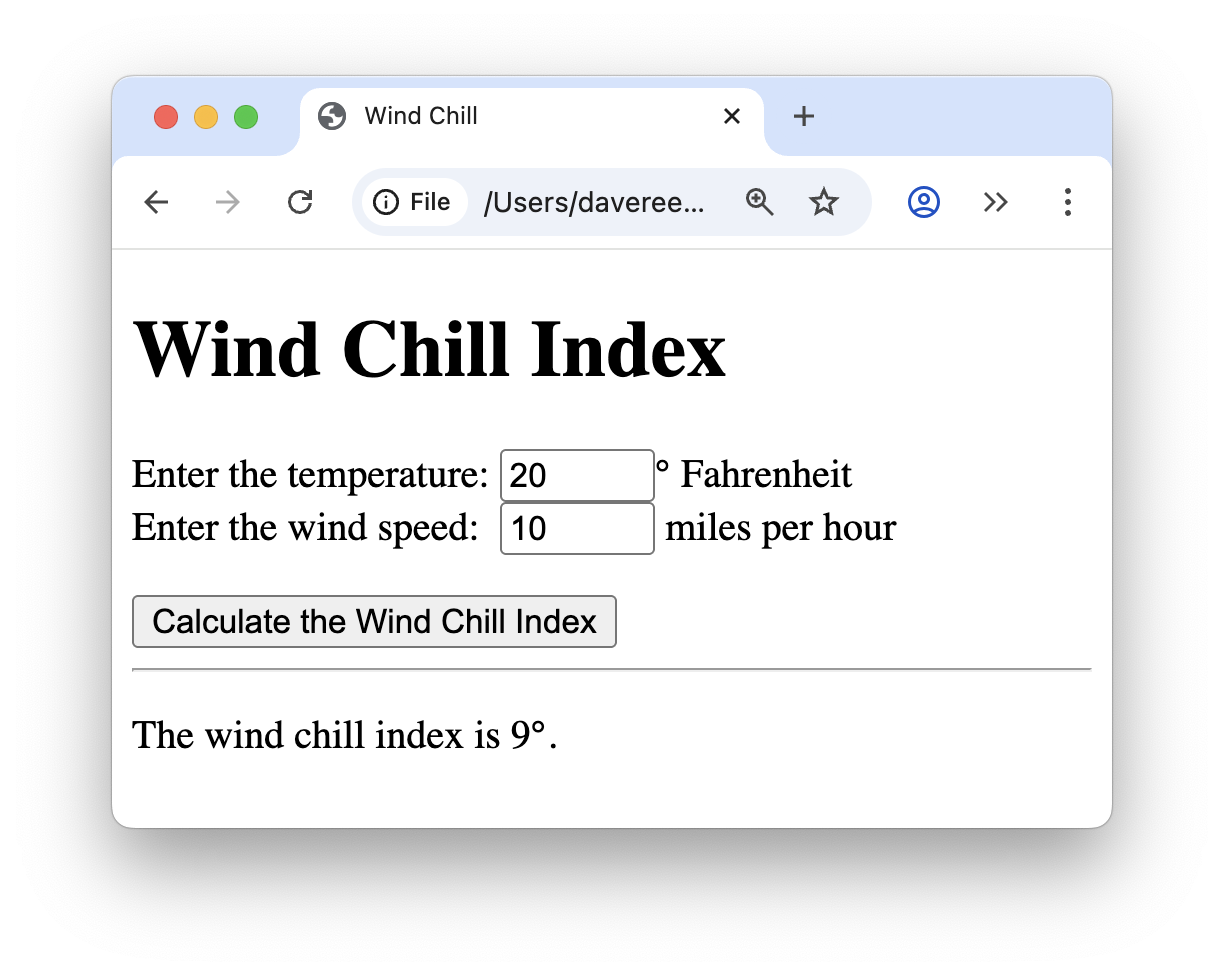

Create a Web page named chill.html that calculates and displays the wind chill index (rounded to the nearest degree). Your page should have two number boxes in which you can enter the temperature and wind speed. If either box is empty or the entered temperature is 50 or above, an appropriate warning message should be displayed. Otherwise, the wind chill index should be calculated and displayed. For example,

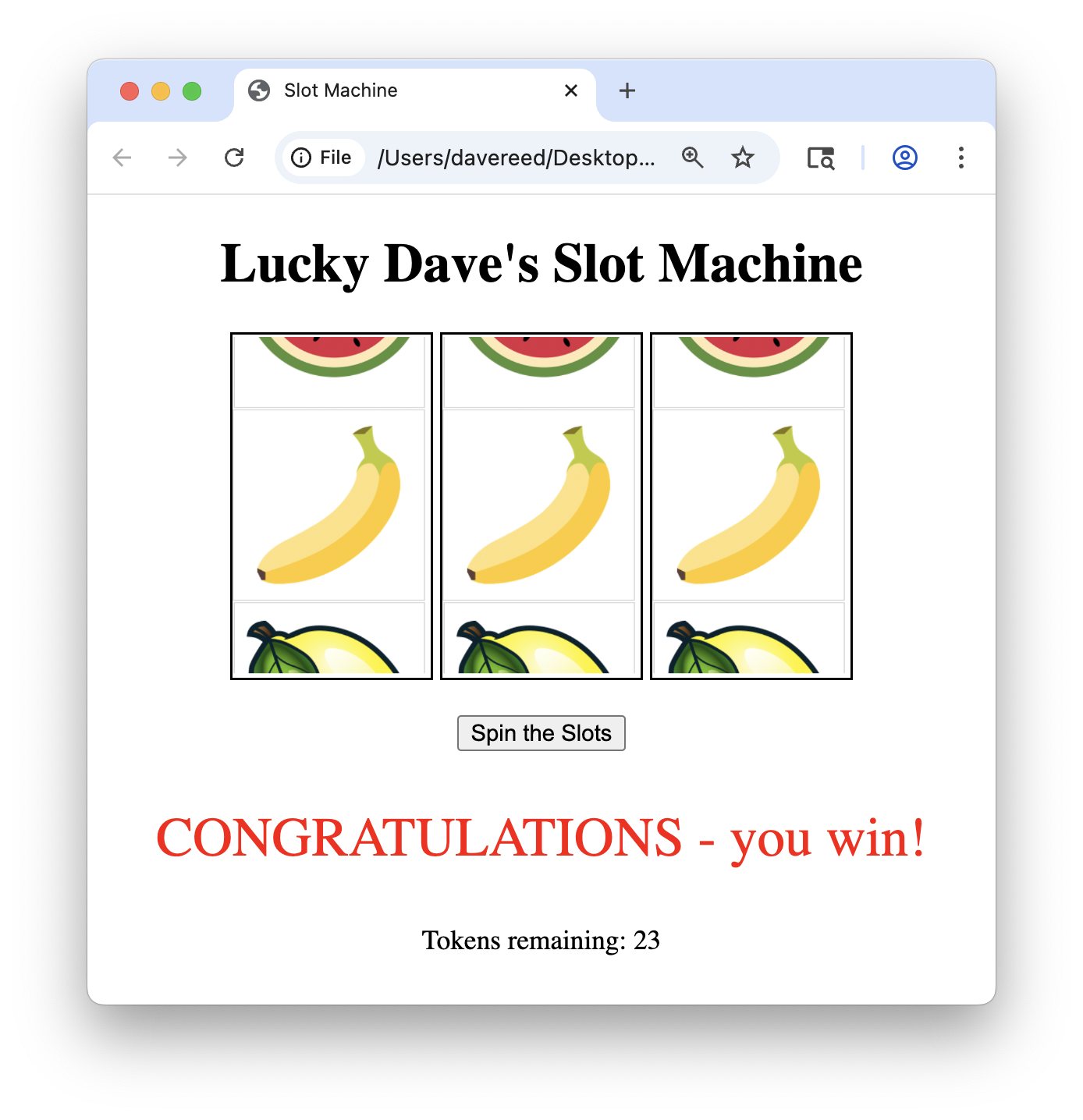

PROJECT 8.D: A slot machine, also known as a one-armed bandit, is a gambling device that involves three or more random images called slots. When you pull a mechanical arm or push a button, these slot images rotate at random. If the slot images all match at the end of the spin, the player wins; otherwise, they lose.

Create a Web page named slots.html that simulates the functionality of a simple slot machine. Your page should have three images side-by-side and a button below that initiates a spin of those images (as shown below). It should recognize a winning spin (when all three images are identical) and keep track of the player's tokens as they play the game. For example,

To help organize this task, it is strongly recommended that you follow these steps:

- To start, build a simplified version of the page with the three images and the button. When the button is clicked, each of the three

imgelements should be assigned a random source file, selected from four choices. If all three random images are the same, the message: "YOU WON!" should be displayed in the page in a large, red font. If not, no message should be displayed. Generic slot images are accessible at the Web addresses listed below, but you should feel free to use your own images if you prefer.https://freecsc.com/Images/lemon.png https://freecsc.com/Images/cherry.png https://freecsc.com/Images/banana.png https://freecsc.com/Images/melon.pngHint: selecting random slot images is not all that different from selecting random dice images, so the dice pages we have studied should be good models for this new page. For determining when the three images are identical, you will need an if statement with a Boolean test that uses the AND operator (&&). - Modify your page so that it keeps track of the player's tokens in a global variable. When the game begins, the number of tokens should start at 20. Each spin of the slots should cost the player 1 token. If all three slot images match, the player wins 14 tokens (for a net gain of 13 tokens on the winning spin). The updated tokens should be displayed in the page after each spin.

- Currently, you can continue playing even after the number of tokens becomes zero or negative. Any smart casino owner would put a stop to this immediately. Add code to the page that verifies you have tokens before allowing you to play. If you have no tokens, a warning message should appear in the page; otherwise, the spin can take place as before.

As is the case with all organized gambling, the odds here favor the house. Since there are four different images that can appear in a slot, there is a 1 in 16 chance of all three slots coming up the same. Thus, you would expect (in the long run) for the player to win 1 out of every 16 spins. Consequently, the payoff of 13 tokens does not offset the 16 token cost of the spins. As a result, you are more likely to lose money (in the long run) than win money. Perform numerous simulations with your Slots page to see if this pattern holds.