C2: The World Wide Web

The Web is more a social creation than a technical one. I designed it for a social effect — to help people work together — and not as a technical toy. The ultimate goal of the Web is to support and improve our weblike existence in the world. We clump into families, associations, and companies. We develop trust across the miles and distrust around the corner. — Tim Berners Lee

If this were a traditional science, Berners-Lee would win a Nobel Prize. What he's done is that significant. — Eric Schmidt

To many people, the World Wide Web is the face of computing. It provides access to vast amounts of information, to companies and their products, and to communication tools that connect people with friends and family around the world. Far from being a static repository of information, the Web is a dynamic, growing and evolving medium through which people can access resources and contribute content. With a little knowledge, anyone can develop Web pages and publish them to the world, becoming Web authors and online influencers. The Web has grown exponentially since its inception in 1990, with the total number of Web pages available today estimated to be in the hundreds of trillions. Of course, that volume of material introduces challenges — how do you find relevant material among all the junk on the Web, and how do you get your voice heard when you publish your ideas or products on the Web?

This chapter provides an overview of the Web, which will be expanded on in future chapters. It begins by distinguishing the Web from the Internet, since the two are so often conflated in people's minds. The history of the Web, in particular the contributions of Tim Berners-Lee in creating and championing it, are discussed, as well as the role that search engines such as Google play in making the Web usable. Finally, the technical aspects of how the Web works are described in easily understandable terms. This includes the roles of Web browsers and servers, as well as the protocols (HTML and HTTP) that make it possible for people to access and contribute to the vast store of resources that is the Web.

Web vs. Internet

Despite a common misconception, the World Wide Web and the Internet are not the same thing. As you will learn in Chapter C3, the Internet is a vast, international network of computers. In the same way that an interstate highway crosses state borders and links cities, the Internet crosses geographic borders and links computers. The physical connections may vary from high-speed dedicated cables (such as cable-modem connections) to slow but inexpensive phone lines, but the effect is that a person sitting at a computer in Omaha, Nebraska is able to share information and communicate with a person in Osaka, Japan (FIGURE 1). The Internet traces its roots back to 1969 when the first long-distance network was established to connect computers at four U.S research universities.

FIGURE 1. Internet users around the world (Ketut Subiyanto/Marcus Aurelius/Ekaterina Bolovtsova/Jopwell/Ekaterina Bolovtsova/Pexels).

Whereas the Internet is made up of hardware (computers and the connections that allow them to communicate), the World Wide Web is a collection of software that spans the Internet and enables the interlinking of documents and resources (FIGURE 2). The basic idea for the Web was proposed in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee of the European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN). To allow distant researchers to share information more easily, Berners-Lee designed a system through which documents — even those containing multimedia elements, such as images and sound clips — could be interlinked over the Internet. Using well-defined rules, or protocols, that define how pages are formatted, documents could be shared across networks on various types of computers, allowing researchers to disseminate their research broadly. With the introduction of easy-to-use graphical browsers for viewing documents in the mid-1990s the Web became accessible to a broader public, resulting in the World Wide Web of today.

FIGURE 2. Internet vs. World Wide Web.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.1: True or False? The terms "Internet" and "World Wide Web" refer to the same entity.

History of the Web

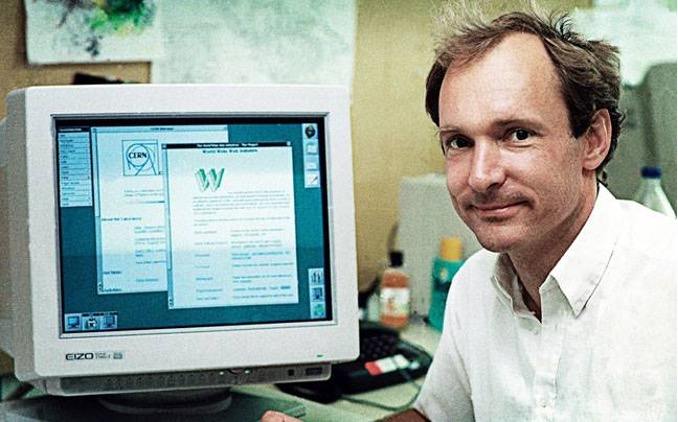

Although Internet communications among universities and government organizations were common in the 1970s and 1980s, the Internet did not achieve mainstream popularity until the early 1990s, when the World Wide Web was developed. The Web, a multimedia environment in which documents can be seamlessly linked over the Internet, was the brainchild of Tim Berners-Lee (1955-), pictured in FIGURE 3. During the 1980s, Berners-Lee was a researcher at the European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN). Because CERN researchers were located across Europe and used different types of computers and software, they found it difficult to share information effectively. To address this problem, Berners-Lee envisioned a system in which researchers could freely exchange documents, regardless of their locations and the types of computers they used. In 1989, he proposed the basic idea for the Web, suggesting that documents stored on Internet-linked computers could be linked so as to make navigating from one to another simple.

FIGURE 3. Tim Berners-Lee (CERN, 1994).

Although Berners-Lee's vision for the Web was revolutionary, his idea was built upon a long-standing practice of linking related documents to enable easy access. Books containing hypertext (interlinked text and media) have existed for millennia. This hypertext might tie a portion of a document to related annotations, as in the Jewish Talmud (first century B.C.), or might provide links to nonsequential alternate story lines, as in the Indian epic Ramayana (third century B.C.). The concept of an electronic hypertext system was first conceived in 1945, when presidential science advisor Vannevar Bush (1890-1974) envisioned designs for a machine that would store textual and graphical information in such a way that any piece of information could be arbitrarily linked to any other piece. The first small-scale computer hypertext systems were developed in the 1960s and culminated in the popular HyperCard system that shipped with Apple Macintosh computers in the late 1980s.

Berners-Lee was innovative, however, in that he combined the key ideas of hypertext with the distributed nature of the Internet. Documents could be stored on computers across the Internet and logically linked regardless of location. His design for the Web relied on two different types of software running on Internet-connected computers. The first kind of software executes on a Web server, a computer that stores documents and "serves" them to other computers that want access. The second kind, called a Web browser, allows users to request and view the documents stored on servers. Using Berners-Lee's system, a person running a Web browser could quickly access and jump between documents, even if the servers storing those documents were thousands of miles apart. Web pages could be linked to other pages based on similar content, regardless of where those linked pages were stored.

In 1990, Berners-Lee produced working prototypes of a Web server and browser. His browser was limited by today's standards, in that it was text based and offered only limited support for images and other media. This early version of the Web acquired a small but enthusiastic following when Berners-Lee made it freely available over the Internet in 1991.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.2: True or False? The original vision of the Web, as well as the first Web browser and server software, are credited to Tim Berners-Lee.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.3: True or False? A Web server is a piece of software that requests and displays Web pages.

Web Growth

The Web might have remained an obscure research tool if others had not expanded on Berners-Lee's creation, developing browsers designed to accommodate the average computer user. In 1993, Marc Andreesen (1971-) and Eric Bina (1964-), of the University of Illinois's National Center for Supercomputing Association (NCSA), wrote the first graphical browser, which they called Mosaic. Mosaic employed buttons and clickable links as navigational aids, making the Web easier to traverse. The browser also supported the integration of images and media within pages, which enabled developers to create more visually appealing Web documents. The response to Mosaic's release in 1993 was overwhelming. As more and more people learned how easy it was to store and access information using the Web, the number of Web servers on the Internet grew from 50 in 1992 to 3,000 in 1994. In 1994, Andreesen left NCSA to found the Netscape Communications Corporation, which marketed an extension of the Mosaic browser called Netscape Navigator. Originally, Netscape charged a small fee for its browser, although students and educators were exempt from this cost. However, when Microsoft introduced its Internet Explorer browser as free software in 1995, Netscape was forced to follow suit. The availability of free, easy-to-use browsers certainly contributed to the astounding growth of the Web in the mid 1990s.

FIGURE 4 documents the growth of the World Wide Web during the last three decades, as estimated by the Netcraft Web Server Survey. It is interesting to note some of the leaps in growth and the events that contributed to those leaps. For example, the jump from 50 Web sites in 1992 to 3,000 Web sites in 1994 can largely be attributed to the widespread adoption of Mosaic, while the next jump to 300,000 sites in 1996 can be attributed to the free availability of Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer. Another advance that increased demand for the Web was the release of JavaScript by Brendan Eich (1961-) and his team at Netscape (see Chapter X4). First introduced in late 1995 and standardized in 1997, JavaScript enabled Web pages to behave dynamically, changing their appearance over time and reacting to user actions. With JavaScript, Web pages could be used to search for items, stream music and video, enter data into forms, and initiate actions at the click of a button. This change in the appearance and functionality of the Web, from static to dynamic pages, is sometimes referred to as Web 2.0.

| Year | Web Sites |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 1,234,228,567 |

| 2016 | 1,083,252,900 |

| 2012 | 676,919,707 |

| 2008 | 175,480,931 |

| 2004 | 52,131,889 |

| 2000 | 18,169,498 |

| 1998 | 4,279,000 |

| 1996 | 300,000 |

| 1994 | 3,000 |

| 1992 | 50 |

FIGURE 4. Web Growth (Netcraft Web Server Survey).

The continued expansion of the Web in the late 1990s and 2000s may be seen as a result of the network effect, a term borrowed from economics that describes when a product or service increases in value as more people use it. When there were only a few Web sites on the World Wide Web, its use was limited to a few, special-interest users. As more business and organizations added Web pages, people began to see the value of the Web and began to use it as an information source. As more people used the Web to seek out information and products, businesses found it worthwhile to invest in a Web site. This cycle continued and the number of Web users and sites grew at a rapid rate through the 2000s.

It is important to recognize that the numbers reported in FIGURE 4 refer to Web sites. Each Web site may contain tens or hundreds or even thousands of pages and files (e.g., images, sound clips, video files). According to Google Inside Search, there were at least 130 trillion individual pages on the Web in 2019, although various sources claim the number of Web pages could be somewhere in the hundreds of quadrillions.

The late 1990s were a dynamic time for the Web, during which Netscape and Microsoft released enhanced versions of their browsers and battled for market share. Initially, Netscape was successful in capitalizing on its first-mover advantage — in 1996, approximately 75% of all operational browsers were Netscape products. By 1999, however, Internet Explorer had surpassed Navigator as the most used browser. Finding it difficult to compete with Microsoft, Andreesen relinquished control of Netscape in 1999, selling the company to AOL for $10 billion in stock. Internet Explorer dominated the browser market for the next decade, until it was surpassed in popularity by the Google Chrome browser in 2012. By the end of 2024, Chrome held more than 67% of the browser market, with Apple Safari a distant second at 18%. Other browsers, including Microsoft Edge (5%), Mozilla Firefox (3%), Samsung Internet (2%), and Opera (2%), continue to have small but dedicated user communities [StatCounter.com]. In addition, the software industry offers numerous others to satisfy niche markets. These include text-based browsers for environments that don't support graphics and text-to-speech browsers for vision-impaired users.

The Web's development is now guided by a not-for-profit organization called the World Wide Web (W3) Consortium, which was founded by Tim Berners-Lee in 1994. The W3 Consortium maintains and regulates Web-related standards and oversees the design of Web-based technologies, relying mainly on volunteer labor from technically qualified and interested individuals.

Interesting Web Facts (Forbes Advisor, 2024)

Interesting Web Facts (Forbes Advisor, 2024)

- It has been estimated that approximately 250,000 new Web sites are created each day. That comes down to 3 new Web sites a second. So, if you read at the average rate (238 words per minute), in the time it takes to read "Another new Web site," another new Web site has been created.

- E-commerce, business conducted via the Web, accounts for around 16% of the total U.S. economy. In 2023, U.S. e-commerce sales totaled more than $1 trillion, with Amazon dominating the sector by amassing 37.6% of those sales. The second-place retailer, Walmart, had only 6.4% of e-commerce sales.

- In 2023, more than 59% of all Web traffic came from mobile devices. Apple is the most popular smartphone brand in the U.S., accounting for 50% of the market share. Samsung is second at 27%.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.4: True or False? Microsoft marketed the first commercial Web browser.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.5: True or False? Google Chrome is the most popular Web browser in the world today.

Search Engines

The initial growth of the Web was largely organic. Companies and organizations purchased computers, installed Web server software, and posted Web sites on their own servers. In the mid 1990s, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) began to provide Web server space to customers, so that individuals could create and post their own Web sites. However, the Web was a bit like the Wild West in that there was little structure or organization to the growth. If you knew the Web address of a page you were interested in, you could enter that address and view the page. However, finding pages without knowing the address was challenging. Sites were eventually developed that catalogued popular sites and so served as a limited index of the Web (or, at least, a small portion of the Web). However, these indexes were dependent on individuals to identify important sites and organize them into an alphabetical index. This approach would not scale as the Web grew.

As the Web increased in size, search engines such as Yahoo Search, Infoseek and AltaVista were developed, which allowed to enter a word or phrase, and the search engine would locate pages that contained that word/phrase. These search engines utilized spiders, or Web crawlers — programs that traversed the Web, cataloging pages to match against the search words. Unfortunately, these searches engines did not always produce high quality results. For example, suppose a user entered the phrase "Cubs game" in the search engine, wishing to know the score of today's baseball game. If the search engine reported every page that contained those words, it would likely report many pages about baby bears and games of all sorts. Finding the score among all those results might prove difficult.

The Google search engine began in 1996 as a research project by graduate students Sergey Brin (1973-)and Larry Page (1973-) at Stanford University (FIGURE 5). Their goal was to develop a search engine that was easy to use and returned high quality results. Brin and Page developed Google's PageRank algorithm, which is used (along with various other techniques) to produce high quality search results. The PageRank algorithm ranks pages based on their perceived value and trustworthiness. If a page is linked to by many other pages, that suggests that people find its contents valuable and trustworthy. In a circular fashion, the trustworthiness of the linking pages can be considered, since being valued and trusted by a valuable/trustworthy page means more than being linked to by an unknown page. Brin and Page also revolutionized how search engines made money, selling ads to advertisers based on the search words and charging based on clickthrough. For example, a shoe store might pay to advertise only when a user enters "shoe" or "footwear" as search words. Likewise, they would be charged based on how often users clicked on the ad to go to the store's Web site. It is interesting to note that Stanford University allowed Brin and Page to freely take their thesis work and form Google in 1998. In gratitude, they donated the patent for the PageRank algorithm to Stanford then licensed that patent for $336 million in stock.

FIGURE 5. Larry Page and Sergey Brin (Ehud Kenan/Wikimedia Commons, 2003).

Today, Google is by far the most popular search engine worldwide (FIGURE 6).

| Search Engine | Worldwide Market Share |

|---|---|

| 90.01% | |

| bing | 3.95% |

| Yandex | 2.34% |

| Yahoo! | 1.35% |

| Baidu | 0.81% |

| DuckDuckGo | 0.65% |

FIGURE 6. Search engine market share, as of September 2024 (StatCounter.com).

Interesting Google Facts (Forbes Advisor, 2024)

Interesting Google Facts (Forbes Advisor, 2024)

- The name Google is a play on googol, which is a math term for the number 10100 (or, 1 followed by 100 zeros). The original name for the search engine, proposed by Brin and Page, was BackRub.

- 92% of global Web traffic comes from Google. In other words, more than nine out of ten visits to a Web site are a result of finding that site through a Google search.

- It has been estimated that approximately 4.91 billion people worldwide use Google. Given that the world population is 8.18 billion (as of October 2024), this means 60% of people in the world use Google!

- On a given day, approximately 8.55 billion Google searches are conducted. That is nearly 100,00 searches per second! Interestingly, Google estimates that 1 out of 6 searches is a question that has never been asked before.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.6: True or False? The PageRank algorithm is used by the Google search engine to rank search matches by relevance and trustworthiness.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.7: What role do spiders (or Web crawlers) play in making search engines work?

How the Web Works

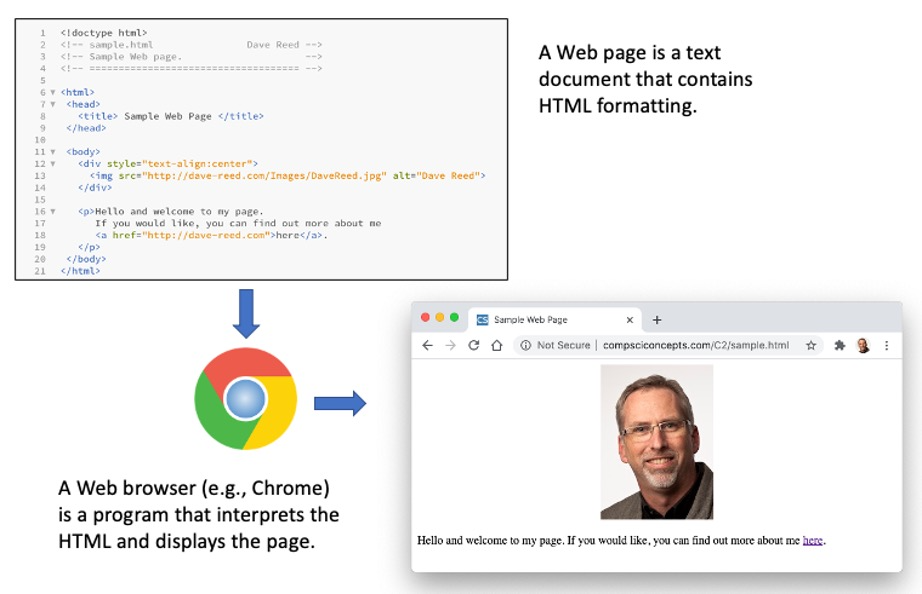

A Web page is nothing more than a text document that contains formatting information in a language called HTML (HyperText Markup Language). As you will see in Chapter X2, all you need to create a Web page is a simple text editor and familiarity with the HTML language. To view a Web page in which HTML formatting is properly applied, however, you need a computer program known as a Web browser. The job of a Web browser is to access a Web page, interpret the HTML formatting information, and display the formatted page accordingly (see FIGURE 7).

FIGURE 7. A Web browser interprets HTML instructions and formats text in a page.

The four most popular browsers on the market today are Google Chrome, Apple Safari (Macs only), Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft Edge (Windows only). Most modern computers are sold with one or more of these browsers already installed (FIGURE 8).

| Web Browsers | Market Share | Web Hosting Providers | Market Share | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Chrome | 65.2% | Amazon Web Services (AWS) | 33.6% | |

| Apple Safari | 18.6% | Google Cloud | 9.4% | |

| Microsoft Edge | 5.2% | IONOS | 5.0% | |

| Mozilla Firefox | 2.7% | GoDaddy | 4.2% | |

| Samsung Internet | 2.6% | EIG | 1.3% |

FIGURE 8. Search engine & Web hosting global market shares (Statista Market Insights, September 2024).

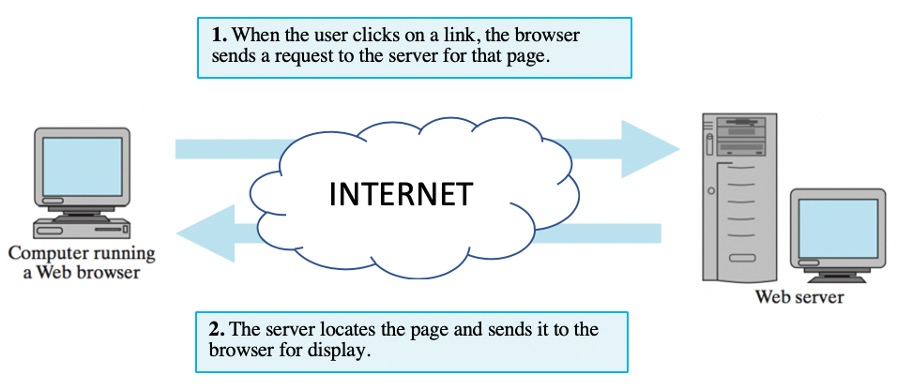

What makes the Web the "World Wide" Web is that, rather than being limited to a single computer, pages can be distributed on computers across the Internet. A Web server is an Internet-enabled computer that executes software for providing access to Web documents. When you request a Web page, either by typing its name in your browser's Address box or by clicking a link, the browser sends a request over the Internet to the appropriate server. The server locates the specified page and sends it back to your computer (FIGURE 9).

FIGURE 9. The roles of the Web browser and Web server.

Web Addresses

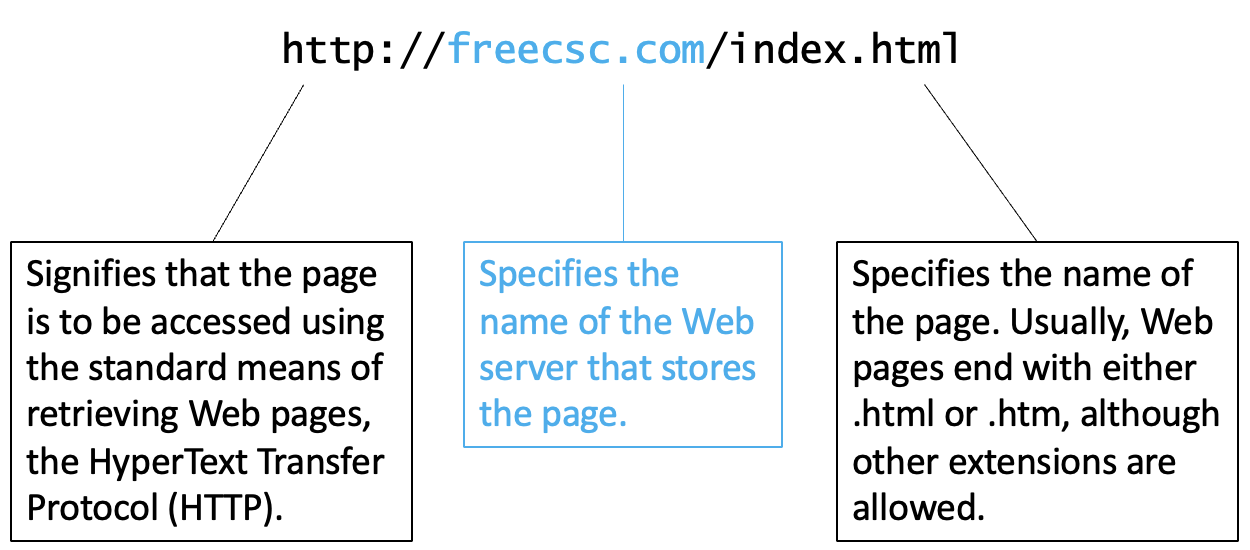

Web pages require succinct and specific names so that users can identify them and browsers can locate them. For this purpose, each page is assigned a Uniform Resource Locator, or URL. For example, the home page for this book has the following URL, also known more informally as its Web address (FIGURE 9).

FIGURE 10. The components of a URL (or Web address).

A Web address begins with the protocol prefix https://, which specifies that the HyperText Transfer Protocol should be used in communications between the browser and server. The 's' in https:// further specifies a secure HTTP connection, which uses encryption to protect the data being sent. The rest of the address specifies the location of the desired page. Immediately following https:// is the server name, identifying the Web server on which the page is stored followed by the file name. If the Web pages are organized into directories on the server, then the file name may be further broken down into components, based on the directory structure. For example, the Web address https://freecsc.com/X2/simple.html refers to the Web page named simple.html that is stored in the X2 directory on the Web server freecsc.com.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.8: In the Web address http://dave-reed.com/index.html, which part identifies the Web server where the page is stored?

Web Protocols

The World Wide Web relies on protocols to ensure that Web pages are accessible to any computer, regardless of the machine's hardware, operating system, browser, or location. In diplomatic circles, a protocol defines the rules that govern affairs of state or diplomatic relations. Web protocols similarly define the rules for how Web pages are to be interpreted and how communication is to take place between a Web browser and server. The protocols that make the Web work are the HyperText Markup Language (HTML) and the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

Web Language: HTML

Web developers define the content of Web pages using HTML, the HyperText Markup Language. HTML defines a collection of character sequences, known as tags, that have special meaning to the browser. For example, the tags <b> and </b> specify to the browser that the enclosed text is to be displayed in a bold font. Likewise, the tags <h1> and </h1> specify a heading that appears in a large, bold font, while <hr> specifies a horizontal rule (or line) that divides sections in the page. In addition, other elements can be embedded within a page, such as images (using the <img> tag) and hyperlinks (using the <a> tag). Part of a Web browser's job is to read HTML tags, interpret their meaning using the rules of the HTML protocol, and display the page content accordingly. You will learn more about HTML in the Explorations chapters (X1-X10).

HTML is an evolving standard, which means that new features are added to the language in response to changes in technology and user needs. The current standard for HTML, as defined by the World Wide Web Consortium, is HTML5. There may be subtle differences among browsers, but all Web browsers understand the same basic set of tags and display text and formatting similarly. Thus, when an author places an HTML document on a Web server, all users who view the page should see the same formatting, regardless of their computers or browser software.

Web Communication : HTTP

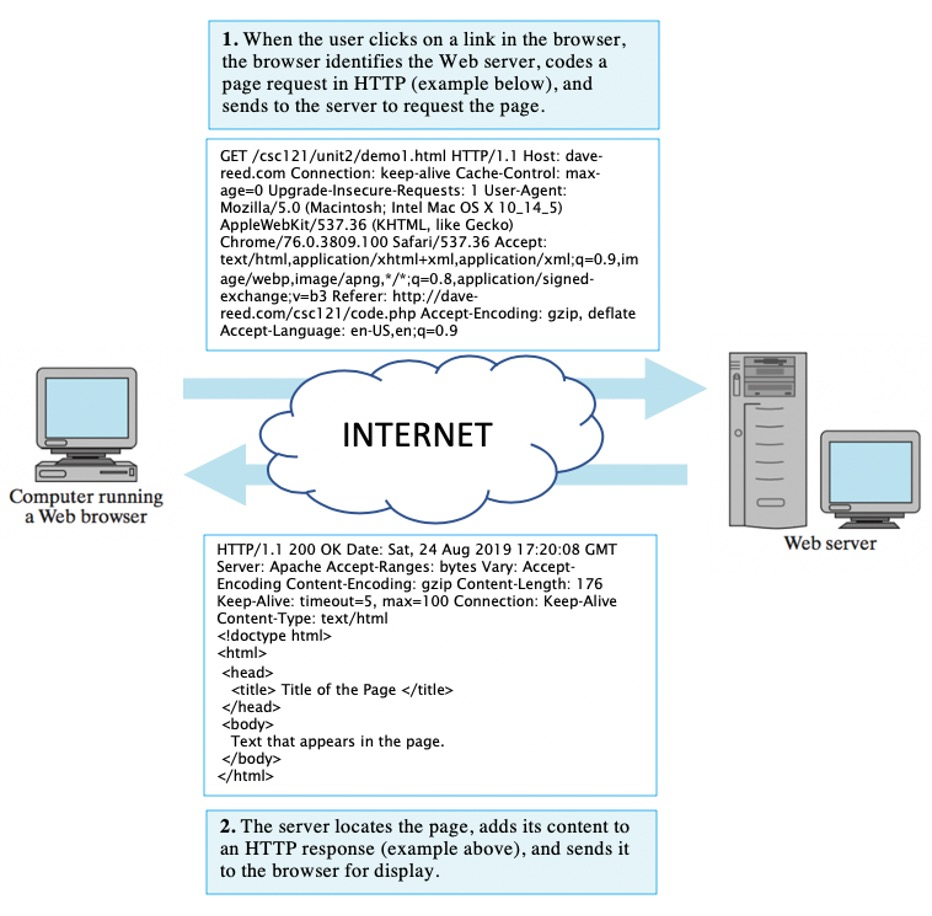

To a person "surfing" the Web, the process of locating, accessing, and displaying Web pages is transparent. When the person requests a particular page, either by entering its location into the browser's Address box or by clicking a link, the new page is displayed in the browser window as if by magic. In reality, complex communications are taking place between the computer running the browser and the Web server that stores the desired page. When the person requests the page, the browser first extracts the Web server name and page name from the Web address (as in FIGURE 9). Once the server name has been extracted, the browser sends a message to that server over the Internet and requests the page. The Web server receives the request, locates the page within its directories, and sends the page's contents back in a message. When the message is received, the browser interprets the HTML formatting information embedded in the page and displays the page accordingly in the browser window.

The protocol that determines how messages exchanged between browsers and servers are formatted is known as the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP). FIGURE 11, which is a more detailed version of the browser/server interaction from FIGURE 8, shows the actual HTTP messages that are exchanged as the result of a clicked link. Note that the HTTP message that requests a page begins with the command GET and includes information that can be used by the server to locate the page and retrieve it in the appropriate format (e.g., the page's address, the type of document, and the browser version). The HTTP message that is subsequently sent back to the browser includes the HTML content of that page, along with information (e.g., size of the document, data and time it was last modified) that might prove useful when displaying the page.

FIGURE 11. Web browser and server communications (with sample HTTP messages).

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.9: True or False? In the Web address https://freecsc.com/index.html, the prefix https:// specifies that the page is stored on a Web server and should be retrieved using the secure HTTP protocol.

Browser Optimizations: Caching & Cookies

It is interesting to note that accessing a single page might involve several rounds of communication between the browser and server. If the Web page contains embedded elements, such as images or sound clips, the browser will not recognize this until it begins displaying the page. When the browser encounters an HTML tag that specifies an embedded element, the browser must then send a separate HTTP message to the server requesting the item. Thus, loading a page that contains 10 images will require 11 interactions between the browser and server—one for the page itself and one for each of the 10 embedded images.

To avoid redundant and excessive downloading, browsers use a technique called caching. When a page or image is first downloaded, it is stored in a temporary directory on the user's computer. The next time the page or image is requested, the browser first checks to see if it has a copy stored locally in the cache, and, if so, whether the copy is up to date. This is accomplished by adding a timestamp to the HTTP message. The timestamp is just the data and time that the cached page was stored. When the server receives the request, it compares the timestamp of the cached page with the timestamp of the page stored on the server. If the cached page is more recent, then the server simply responds with an HTTP message instructing the browser to display its cached copy. If the server version is newer, however, then it is sent back to the browser to ensure that the up-to-date version of the page is displayed.

Note that caching does not reduce the number of messages that must be sent between the browser and server. Each page request still requires an HTTP message to the server and a subsequent message back to the browser. However, caching can save time when the cached copy is up-to-date, since only a confirmation message is returned as opposed to downloading the page all over again. When the requested item is a large image or video clip, this savings can be significant.

Caching relies on the browser being granted access to a directory for storing the cached pages. This limited access to the user's file system is safe and is built into all modern browsers. Beyond that, however, browsers are not allowed access to any other local files. One of the design goals of the Web was to make the physical location of the documents irrelevant — the user need not even pay attention to where documents are stored since the logical relationships between documents is what defines Web connectivity. As a result, surfing the Web often involves jumping from one page to another, accessing documents on Web sites whose owners may not even be known to you. If accessing a Web page from an unknown site had the potential to make your personal files visible to others and vulnerable to destruction, you would think twice before ever using the Web. As a result, Web browsers are built so that the files on the local computer (other than the cache directory) are not accessible.

There is a small loophole in Web browser file access that is both useful and potentially annoying to users. Cookies are small, special-purpose files that can be stored by the browser on your computer when you visit a Web site. For example, when you visit a commercial site, that Web server at that site can request that the browser store a small file on your computer with information about you (the date and time you visited the site, the items you searched for, etc.). The next time you visit that site, the browser will include this cookie file with each page request. This is how Web sites know who you are when you return to a site or remember what was in your shopping cart when you last left the site. Cookies are safe, since the browser only shares the cookie file with the Web server that originally stored the cookie. Cookies can add to the convenience of Web surfing by customizing your Web experience and saving you from repeatedly entering data. Cookies can also be intrusive, as you may not want the site to remember sensitive information or browsing history. Most browsers allow you to limit cookies, although many Web sites do not function as smoothly if cookies are disabled.

Beginners often confuse caching and cookies. It is true that both store information on the user's computer in hidden directories. However, their purposes are quite distinct. Caching stores copies of entire pages and documents, which are used by the browser to avoid redundant downloading. Without caching, Web sites would look the same but might be slower to load. Cookies, on the other hand, are small data files that are stored by the browser at the direction of the server. They provide additional functionality to pages, since a Web site can store information about your past visits and customize your next visit based on that stored information.

✔ QUICK-CHECK 2.10: True or False? In most Web browsers, cookies are used to save local copies of downloaded pages and files in order to save time when they are accessed again.

Chapter Summary

- The Internet is hardware — a vast, international network of computers that traces its roots back to the 1960s. The World Wide Web is a collection of software that spans the Internet and enables the interlinking of documents and resources.

- A Web page is a text document that contains additional formatting information in a language called HTML (HyperText Markup Language). Web pages are stored on computers known as Web servers and viewed with programs known as Web browsers.

- A Web address, or Uniform Resource Locator (URL), uniquely identifies the Web server and location of a page so that it can be accessed by a browser.

- First proposed by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, the World Wide Web is a multimedia environment in which documents can be seamlessly linked over the Internet.

- The Web relies on two different types of software running on Internet-enabled computers: a Web server stores documents and "serves" them to computers that want access; a Web browser, allows users to request and view the documents stored on servers.

- Although working prototypes of the Web were available in 1990, the growth of the Web was slow until the introduction of graphical browsers (NCSA Mosaic in 1993, Netscape Navigator in 1994, and Microsoft Internet Explorer in 1995), which better integrated multimedia elements and made navigation simpler.

- The explosive growth of the Web can be attributed to the network effect since the utility and value of the Web increased as more people used it.

- The Web's development is now guided by a not-for-profit organization called the World Wide Web (W3) Consortium, which was founded by Berners-Lee in 1994.

- Search engines, such as Google, utilize spiders — programs that crawl the Web to index pages. In 2019, Google had indexed more than 130 trillion Web pages.

- The Google search engine utilizes a patented PageRank algorithm to rank the relevance and trustworthiness of search matches, enabling it to produce high quality search results.

- The protocols most central to the Web interactions are HTML and HTTP. The Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) defines the content of Web pages, whereas the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) determines how messages exchanged between browsers and servers are formatted.

- To avoid repeatedly downloading the same Web page over and over, browsers may cache pages.

- Cookies are small data files that are stored by the browser at the request of a Web server, enabling that server to subsequently access the files when the user returns to the site.

Review Questions

- It has been said that the Internet could exist without the Web, but the Web couldn't exist without the Internet. Why is this true?

- What is a Web server, and what role does it play in the World Wide Web?

- Consider the following fictitious URL: https://www.acme.com/products/info.html. What does each part of this URL (separated by slashes) specify?

- What is hypertext? How are the key ideas of hypertext incorporated into the Web?

- What specific features did the Mosaic browser include that were not available in earlier browsers? How did these features help make the Web accessible to a larger audience?

- What does HTTP stand for, and what is its role in facilitating Web communications?

- The World Wide Web Consortium maintains and regulates Web-related standards and oversees the design of Web-based technologies. Visit its Web site (w3.org) to review the organization's goals and list of technologies under active development. Describe three technologies (other than HTML and HTTP) whose development is managed by the World Wide Web Consortium.

- How does caching improve the performance of a Web browser? Does caching reduce the number of interactions that take place between the browser and the Web server?

- Describe the role of cookies in Web browsers. What are the benefits of cookies? What are the potential dangers for users?

- Use a search engine to research and answer the following questions. Identify the site at which you obtained your answer, as well as the search parameters you used to locate the page.

- Who invented the programming language Python?

- In what year did the Battle of Hastings take place?

- Who won the Academy Award for best actress in 1996?

- How many number-one hits did the Beatles have?